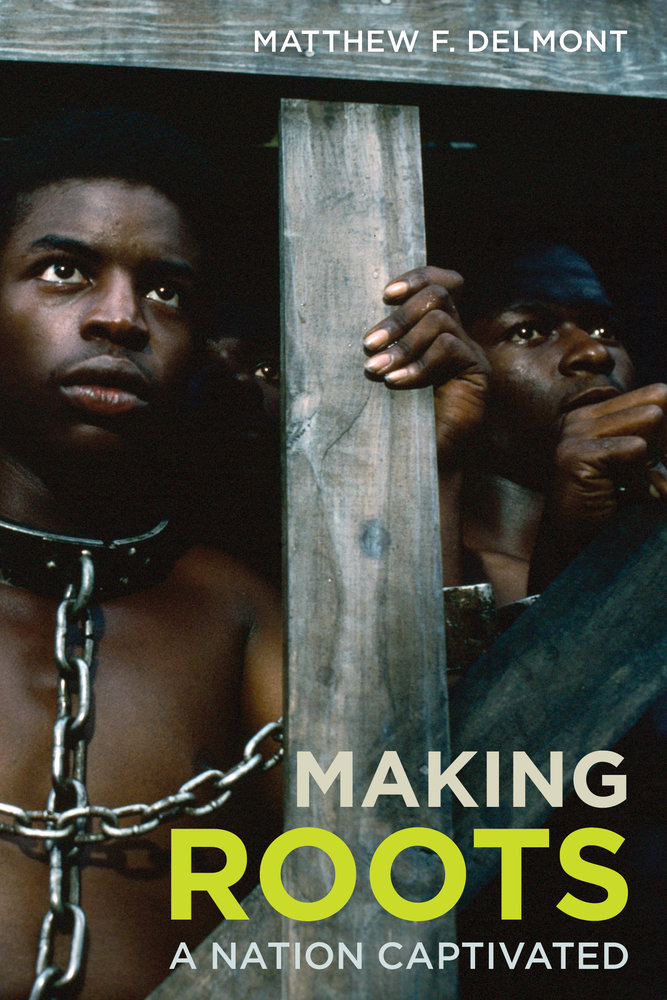

Making Roots: A Nation Captivated, was published in August 2016 by University of California Press. This is the first book length study of Roots.

Making Roots: A Nation Captivated, was published in August 2016 by University of California Press. This is the first book length study of Roots.

Roots, published by Doubleday in the fall of 1976 and broadcast by ABC in the winter of 1977, was read by millions and watched by millions more, but today, Roots is neither acclaimed by critics nor much studied by academics. Roots fell out of favor in part because Haley’s story started to unravel as soon as it was in print. Haley fabricated parts of his story, paid over half a million dollars to settle a plagiarism suit brought by Harold Courlander, and relied heavily on an editor, Murray Fisher, to finish Roots. Other people were upset with how ABC, Doubleday, Haley, and associated parties seemed to be wringing money from the history of slavery. This explicit commercialization allowed Roots to reach millions of people, but it has made it difficult to see the book or the television series as a serious contribution to our nation’s understanding of the history of slavery.

Still, Roots encouraged more people to engage seriously with the history slavery than anything before or since. Popular and academic reviewers who dismissed the book and television series as too middlebrow or criticized its historical accuracy largely missed the point. Roots asked viewers, across racial lines and national borders, to see slavery as a story about black people and black families and to identify with the sorrow, pain, and joy of enslaved people in ways that were unusual in commercial literature and unprecedented in broadcast television. Roots remains the most popular television miniseries of all time and its success will likely never be duplicated in the contemporary media environment. Producer David Wolper, joked that with so many channels now, “You couldn’t get a 71 share if you had the returning of the Lord.”

Roots began as a book called Before This Anger, which Alex Haley pitched to his agent in 1963. Haley signed a contract the following year to write the book for Doubleday, while he was also finishing work on The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Haley originally planned for Before This Anger to focus on his hometown of Henning, Tennessee in the 1920s and 30s, and to use this nostalgic vision of rural Southern black life as a contrast to the urban unrest and racial tensions of the 1960s. Haley’s vision for the book expanded after family elders told him about someone they called “the Mandingo,” who passed down stories of having been captured in Africa and sold into slavery. This initial family story sent Haley on a research quest motivated both by personal and financial concerns. On a personal level, Haley felt a natural human desire to understand his family’s history. For Haley, like other descendants of enslaved people, this desire for genealogical knowledge was thwarted by the fact that his ancestors had been forcibly uprooted from Africa and treated as property for generations in America. The Middle Passage, where enslaved people were transported from Africa to the New World, both claimed lives and ruptured histories. When Haley eventually identified Kunta Kinte, from the Gambian village of Juffure, as his family’s “original African,” he felt like he had reclaimed something that had been stolen from him.

Haley also understood that searching for and finding Kunta Kinte made for an amazing and lucrative story. Money problems followed Haley for the twelve years he worked on Roots and Haley supported himself during these years by lecturing across the country. Haley was a dynamic speaker and on the lecture circuit he turned his search for his family’s history into a detective story. He described travelling across continents and racing from archive to archive in search of clues. In Haley’s detective story all of the pieces remarkably fell into place so that the stories he heard from his family elders matched up perfectly with legal deeds, shipping records, and Gambian oral histories. Much of what Haley told audiences was true; other parts were exaggerated, embellished, or fabricated. More importantly, Haley’s story of his search for roots captivated audiences. As Haley crisscrossed the country in the late-1960s and early-1970s, he told the story of his search for roots to hundreds of thousands of people, earning five hundred to one-thousand dollars per appearance.

Haley was constantly selling Roots. His busy speaking schedule made it difficult for him to finish his epic book, but the lectures amounted to one of the longest advance promotion tours in the history of publishing or broadcasting. Haley used his storytelling skills, honed in front of lecture audiences, to successfully pitch Roots to Reader’s Digest, which published a condensation of the book in 1974, to producers David Wolper and Stan Margulies, as well as ABC television executive Brandon Stoddard. Whether Haley was speaking to college students, church groups, or television professionals, he understood that audiences responded to Roots, first and foremost, as a good story. Telling and retelling his story taught Haley to focus less on the boundaries between fact and fiction, or between history and literature, and more on making a connection with his audience.

Alex Haley never published another book after Roots. Haley loved talking to people, but found himself overwhelmed by the praise, criticism, and legal troubles Roots generated. “He made history talk,” Jesse Jackson said of Alex Haley at the author’s funeral in 1992. “He lit up the long night of slavery. He gave our grandparents personhood. He gave Roots to the rootless.” In this light, pointing out the flaws in Haley’s family history fells like telling your grandmother she is lying. Fortunately, Haley’s fabrications are only a small part of a much larger, more interesting, and more complicated story of the making of Roots. This book tells that story.